Introduction

You write a line of code:

userService.createUser()

You hit Run. Or you push a commit. Or your CI pipeline deploys it to production.

A few seconds later, real users are creating accounts.

Somewhere between that single line of code and a real human using your system, a lot happens.

Most developers never see this full journey. We work comfortably inside frameworks, SDKs, and cloud dashboards. The deeper layers; operating systems, runtimes, schedulers, memory - quietly do their job.

This post is about pulling back that curtain.

We’ll trace the end-to-end path of code execution: from source code on your laptop to a running process serving production traffic. No magic. No marketing diagrams. Just the layers that actually make software run.

Think of this as building a mental model, one that helps when things break at 2 a.m.

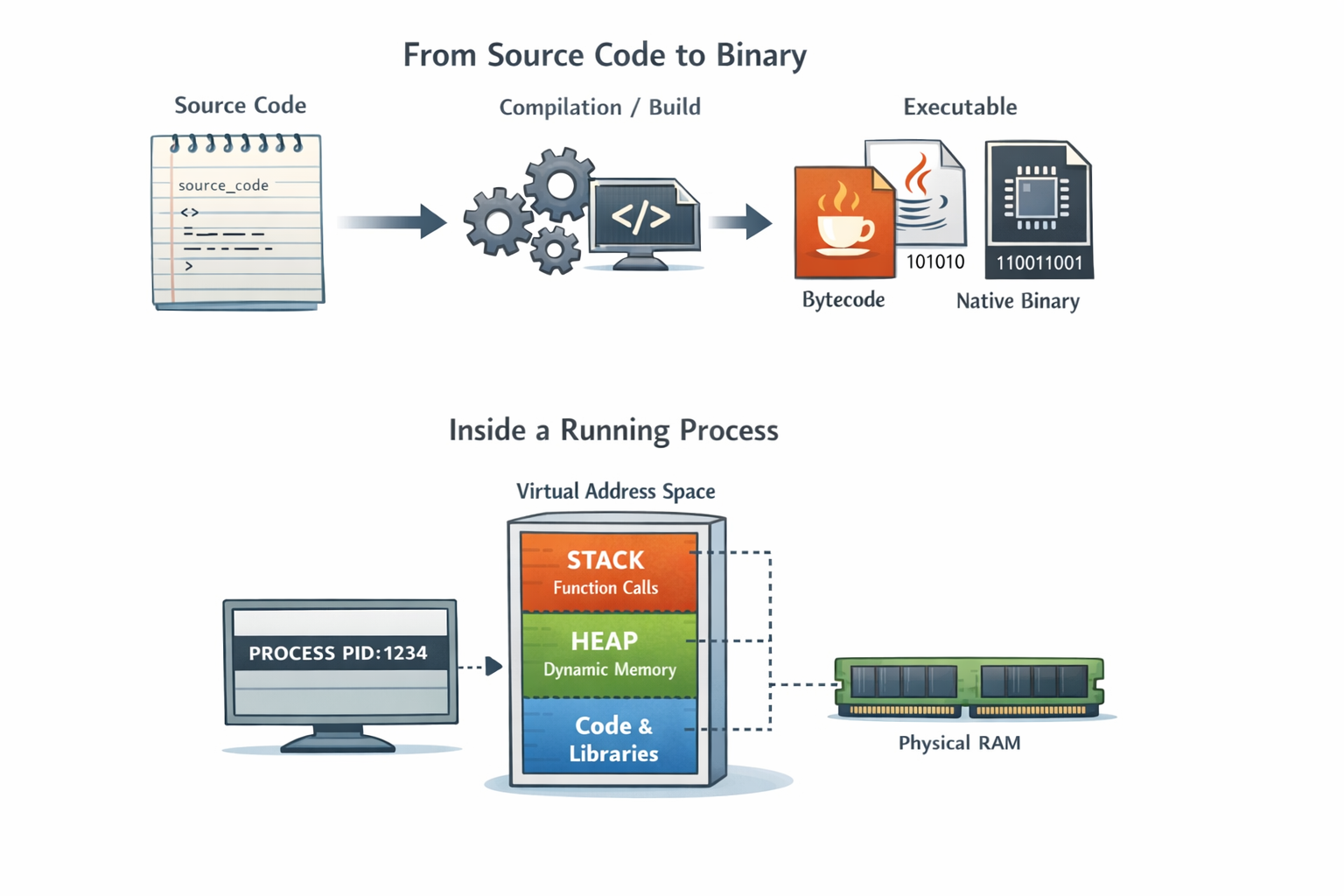

1. From Source Code to Binary

Source code is just text. Plain files full of symbols that make sense to humans.

Machines don’t execute text.

Before anything can run, your code has to be transformed into something the computer understands.

That transformation depends on the language and ecosystem, but conceptually it always looks like this:

- Parsing: Your code is checked for syntax and structure

- Translation: It’s converted into a lower-level representation

- Packaging: The result is bundled into an executable form

In some languages, this produces native machine code, instructions the CPU can run directly.

In others, it produces bytecode, an intermediate format designed to be executed by a runtime like the JVM.

Either way, the output is no longer “code” in the way you wrote it. It’s a file that follows strict rules understood by the operating system.

At this point, you have a program.

But it’s still not running.

2. The Operating System Steps In

When you start an application, you’re really asking the operating system to do something on your behalf.

This is where an important distinction appears:

- A program is a passive file on disk

- A process is a living thing, code in execution

The OS takes your program and creates a process out of it.

That involves several steps, all invisible to most developers:

- Assigning a Process ID (PID)

- Creating an isolated virtual memory space

- Setting up file descriptors (for files, sockets, logs)

- Loading the executable into memory

From the OS’s perspective, your application is no longer “a web service” or “a backend”.

It’s just a process.

And the OS is now responsible for keeping it alive, scheduling it on the CPU, and cleaning it up when it dies.

The transformation from static program files to living processes managed by the operating system

The transformation from static program files to living processes managed by the operating system

3. Memory: Stack, Heap, and Virtual Address Space

Every process believes it owns the entire machine.

This is a lie.

The trick that makes it work is virtual memory.

Each process gets its own private address space, a clean, isolated view of memory. The OS maps that virtual view onto real physical RAM behind the scenes.

Inside that space, memory is typically divided conceptually into regions:

- Stack: Used for function calls and local variables. Fast, structured, and limited

- Heap: Used for dynamically allocated objects. Flexible, powerful, and dangerous if mismanaged

A simple analogy:

- The stack is like a stack of plates: last in, first out

- The heap is like a storage room: you put things wherever there’s space

Memory isolation is why one crashing application usually doesn’t take down the whole system.

Each process lives in its own bubble.

4. Runtime Environment Takes Control

If your application uses a runtime like the JVM, Node.js, or Python; another layer now wakes up.

The runtime is itself just a program, but it has a big job:

- Loading bytecode or scripts

- Managing memory allocation

- Handling garbage collection

- Translating code into CPU instructions

Some runtimes interpret code line by line.

Others use Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation, watching which parts of your code run frequently and compiling them into highly optimized machine code on the fly.

This is why long-running services often get faster over time.

The runtime is constantly balancing performance, safety, and resource usage usually without you noticing.

Until you do.

5. Threads, Scheduling, and the CPU

A process rarely runs as a single stream of execution.

It creates threads, units of work that can run concurrently.

The operating system scheduler decides:

- Which thread runs

- On which CPU core

- For how long

This happens thousands of times per second.

When a thread is paused and another resumes, the OS performs a context switch, saving and restoring registers, memory mappings, and execution state.

Context switching is powerful.

It’s also expensive.

This is why concurrency is hard. More threads don’t automatically mean more performance. They mean more coordination and more opportunities for things to go wrong.

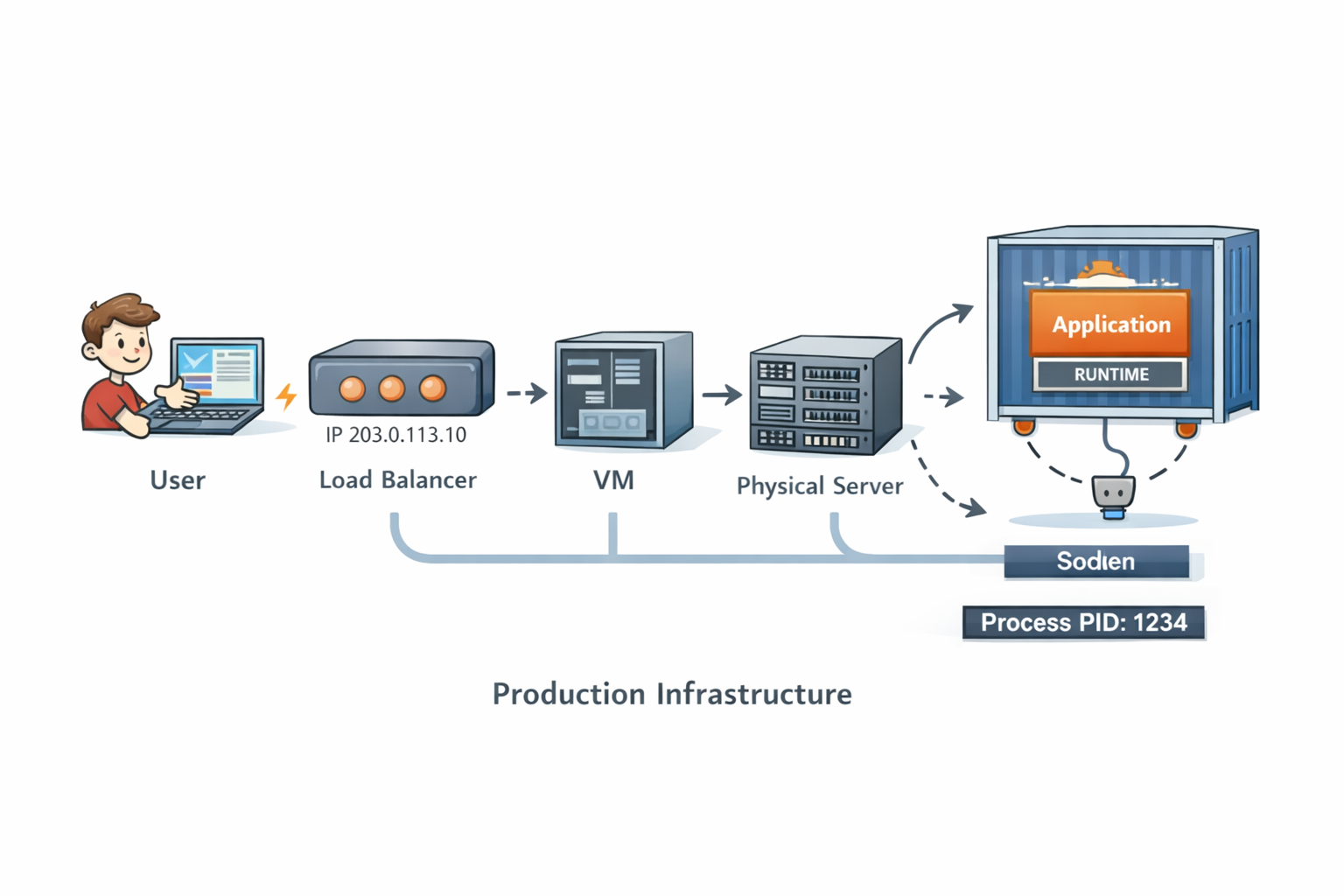

6. From Code to Production Traffic

In production, your process rarely runs alone.

It might live inside:

- A container

- A virtual machine

- A physical server you never see

Modern production infrastructure: containers, orchestration, and distributed systems working together

Containers don’t change how code runs, they change where and how the OS enforces boundaries.

Modern production infrastructure: containers, orchestration, and distributed systems working together

Containers don’t change how code runs, they change where and how the OS enforces boundaries.

When a request hits your system:

- It arrives at a load balancer

- It’s routed over the network

- The kernel delivers it to a socket

- Your process reads bytes from that socket

- A thread wakes up and executes your code

From the outside, it looks instant.

Inside, it’s a carefully choreographed dance across layers.

7. When Things Go Wrong

Production failures feel random because they emerge from interactions between layers.

A small memory leak becomes an out-of-memory kill.

A blocked thread pool becomes a full outage.

A slow disk turns into cascading timeouts.

The system isn’t fragile, it’s complex.

Understanding the layers helps turn “it just crashed” into “this is why it crashed.”

8. Why This Mental Model Matters

Engineers with a strong execution model:

- Debug faster

- Design more resilient systems

- Make better trade-offs

- Stay calm during incidents

They don’t guess.

They reason.

Conclusion

That single line of code you wrote didn’t magically run.

It was compiled, loaded, scheduled, interpreted, optimized, and executed across dozens of layers built over decades.

Software isn’t magic.

It’s abstraction.

And abstraction is only powerful when you understand what’s underneath it.

Great engineers don’t just write code they understand where it runs.